Select Language: tiếng Việt

French - Vietnam conflict

When Vietnam first became independent from China in 939 AD it was called ‘Viet’ and consisted of the area that makes up present day northern Vietnam. Not long after throwing off their Chinese rulers, the Viet people became covetous of the area to their south, which at the time was occupied by the India-influenced Champa Kingdom. A period of aggressive Viet expansionism began and by 1471, their conquest of the Champa Kingdom (current day central Vietnam) was complete.

Not satisfied with their gains, the Viet people began taking control of the Khmer lands north of the Mekong delta in the 1620s. This push southwards at the expense of the Khmers continued until, by 1780, the Viets had seized control of the area now known as southern Vietnam.

In the 19th Century it was the Viets’ turn to be victims of imperialist expansion as France sought to extend its empire into South East Asia. After gaining a foothold in southern Vietnam in the 1860s, the French gradually extended their rule until, by 1883, they had control of the whole country.

Vietnam struggles to mount effective resistance to French until WW2

By the time the Second World War broke out France had governed the whole of Vietnam for nearly 60 years, having gradually extended its rule from just the southern region in the 1860s to the whole country by 1883. For administrative purposes the French had divided the country into the three regions of Tonkin (North Vietnam), Annam (Central Vietnam) and Cochin China (South Vietnam), areas which, together with Laos and Cambodia, made up the colony of Indo China.

French rule had had a strongly negative impact on Vietnam, bringing greater impoverishment and exploitation to its peasants while also undermining the confidence of many of the country’s intellectuals, teachers and imperial bureaucrats in their own culture.

Vietnamese landlords, on the other hand, were given increased power and wealth under the French, thereby ensuring that many from this class would be loyal to the colonial rulers. During the entire period of French rule, the Vietnameselaunched repeated uprisings against their colonial overlords, but never managed to overcome the might of the French military.

In the early 20th century Phan Boi Chau and Phan Chu Chinh emerged as capable nationalist leaders, but neither of them managed to extend their appeal beyond middle class urbanites, the social strata from which they themselves both hailed.

It was not until the arrival of Ho Chi Minh, a nationalist and communist who appealed to many urban people and peasants, that Vietnam had a leader who was able to lead a relatively united front against French rule. Ho, born Nguyen Tat Thanh in a central Vietnamese village in 1890, was raised by a fervently nationalistic father who resigned from his job as a bureaucrat in protest at the French takeover of Vietnam.

First and foremost a pragmatic nationalist and anti-colonialist, Ho did not adopt communism until his demands for Vietnam’s independence were rebuffed by President Woodrow Wilson at the Versailles conference after World War One.

Bitterly disappointed at the American president’s lack of interest in colonial countries’ calls for self determination, Ho, then named Nguyen Ai Quoc (Nguyen the Patriot), searched for a political philosophy that seemed to take seriously the issue of freedom for colonial peoples. He found it in Lenin’s writings and thereafter became a dedicated communist, saying: “only Socialism and Communism can liberate the oppressed nations.” (Young, 1991: p3; Lawrence, 2010: p17)

Despite Ho’s skill as a networker, organiser and orator, he was unable to mount an effective challenge to French rule in Vietnam until the Second World War when events conspired to undermine France’s standing on the world stage and, thereby, create opportunities for Vietnamese nationalists.

The first sign of hope appeared when France was trounced by Germany, the rapid loss denting French confidence and prestige. The situation improved further for Ho when Japanese forces invaded Vietnam in 1940 and promptly demanded that the French colonial government share authority with them on their terms.

Although the French colonial administration was left intact, there was no doubt that the Japanese were directing operations from behind the scenes. With French power in Indo China now fatally weakened, Ho at last could see an opportunity for Vietnamese nationalists to launch a campaign for independence.

In 1941, while hiding out in Pac Bo, a cave in the forests of northern Vietnam, Ho formed the Viet Minh, an anti-French alliance led by communists. Early attacks by the Viet Minh’s fledgling army were crushed, but the new coalition’s brilliant general, Vo Nguyen Giap, bolstered the strength of his fighting force and returned to the battle field with gusto in 1944, notching up a series of impressive victories over French outposts across North Vietnam. After these military successes support for the Viet Minh increased significantly and the coalition was able to gain military control of much of the North.

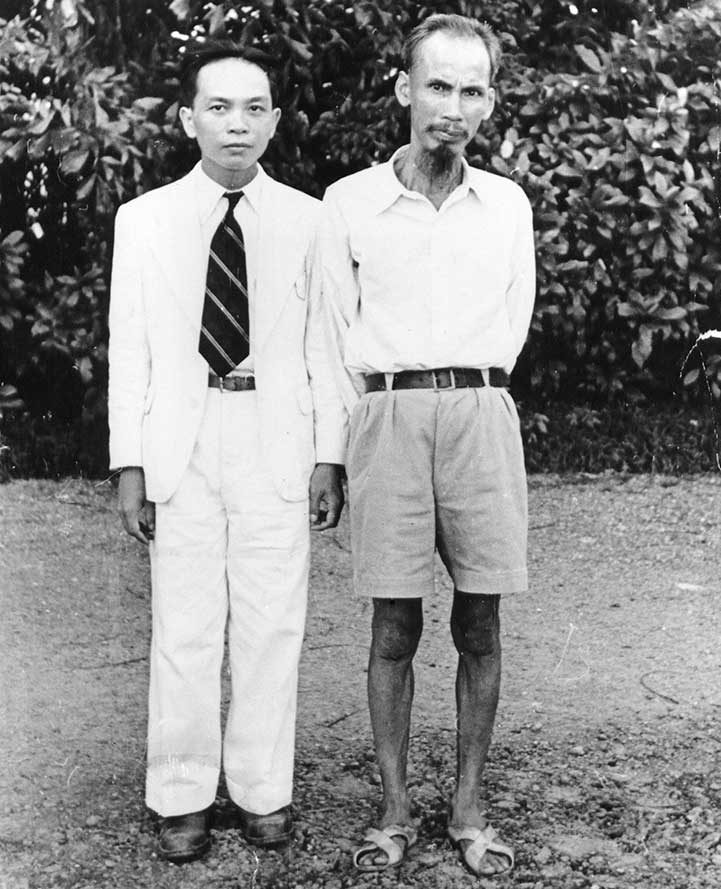

Ho Chi Minh, right, who became president of North Vietnam, poses with Vo Nguyen Giap, minister of the Interior in Ho Chi Minh's provisional government, ca. 1950s. Gen. Giap went on to lead the Viet Minh and North Vietnamese military to defeat both the French and combined U.S.and South Vietnamese forces, culminating in the fall of Saigon in 1975. (AP Photo)

The Viet Minh also implemented some progressive social policies over the course of the Second World War that shored up their support base, especially among poor, rural Vietnamese people. By the time that conflict ended then, Ho and his forces were in a strong position to challenge the returning French. Only in Saigon did the Viet Minh struggle to establish itself as the most dominant of the Vietnamese groups vying to seize power and resist the French.

After World War 2 the French, still smarting from their rapid defeat to Germany on home soil and their forced collaboration with Japanese forces in Vietnam, were in no mood to give up control of their colonies. In the case of Vietnam, they were determined to at least regain control of Cochin China (South Vietnam), their most prized Indochinese possession, even if Tonkin (North Vietnam) and Annam (Central Vietnam) were eventually lost.

Meanwhile the Vietnamese, having been emboldened by the sight of French colonial authorities being forced to share power with the Japanese forces, felt there was no time like the present for staking out a claim for independence.

While compromise solutions seemed plausible with respect to Tonkin and Annam, the two countries were on a collision course over Cochin China, the most prosperous and fertile region of the country. The Vietnamese viewed Cochin China as an integral part of Vietnam and refused to bow to French pressure to allow them to govern it.

A native soldier of the French-Indochinese Union army carries a portable radio set strapped to his back, while Sgt.-Major Poncelet of Ecouviez, France, is signaling his position to the unit commander, during war operations in Viet Minh-held territory, some 25 miles northeast of Saigon, in southern Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh, eager to avoid a war and yet determined to eventually gain full independence for a united Vietnam, signed treaties aimed at placating the French by granting them a continued presence in the country and by delaying full independence. But these deals did little to calm the simmering tensions on the ground between the Viet Minh and the French colonial authorities and their military and civilian backers. These tensions came to a head in 1946 when violent clashes over which side had the right to collect customs duties in Haiphong escalated into a full blown war that was to drag on until 1954.